AC Power Control with Thyristor: Phase Angle Control using triac with PIC16F877A

Principle of Phase Angle Control

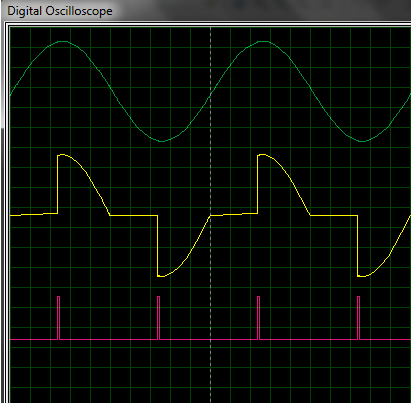

Top - Output Voltage

Bottom - Gate Drive Signal

Image source: Wikipedia (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Regulated_rectifier.gif)

The photo above clearly illustrates phase angle control: output voltage controlled by the gate drive signal applied to a thyristor. What is phase angle control? That is what I'm going to talk about in this article.

Phase angle control is a method of PWM applied to AC input voltages, usually the mains supply. Of course, the AC supply could be from a transformer or any other AC source, but the mains supply is the most common input – this gives the phase angle control method its greatest usefulness. It has of course become quite obvious from the title (and I’m sure most of you reading will already know this) that the purpose of phase angle control is to control or limit power to the load.

The power device used in phase angle controllers is a

thyristor – mostly triacs or SCRs. (There are methods of phase controlling

employing high frequency switching using a MOSFET or IGBT, but here I’ll talk

about phase angle control with thyristors only). The power flow to the load is

controlled by delaying the firing angle (firing time each half-cycle) to the

power device.

We know that the thyristor is a latching device – when the

thyristor is turned on by a gating signal and the current is higher than the

holding current and the latching current, the thyristor stays on, until the

current through it becomes sufficiently low (very close to zero). The thyristor

turns off when current through it becomes zero, as happens at the AC mains zero

crossing. This is the natural line commutation. (Another method of turning the

thyristor off is by forced commutation. I won’t go into that now.) The

assumption here is that the load is resistive and has little to no inductance.

Of course, this is not always the case, as inductive loads are often used.

However, I’ll work with this assumption for now.

Now, with that covered, you should read this article first

before proceeding to the rest of this article:

Zero crossing detection with PIC16F877A: http://tahmidmc.blogspot.com/2012/10/zero-crossing-detection-with-pic16f877a.html

I’ve added the circuit, code and simulation of an example

later in this article. And that uses a triac as the power device. So, from now

on, I’ll just refer to the triac instead of talking about a thyristor in

general.

So, in phase angle control, a gate pulse is sent to the

triac. This is sent at a time between one zero crossing and the next. Without

the gate pulse sent to the triac, right after zero-crossing, the triac is off

and no current flows through it. After a certain time, the gating signal is

given to the triac and it turns on. The triac then stays on until the current

through it becomes zero (natural line commutation). This is at the next zero

crossing. For simplicity’s sake and as usually should be, assume that the

current through the triac (when on) is larger than the latching current and the

holding current. If you didn’t already know this, the latching current is the

current that must pass through the triac right after it is turned on to ensure

that it latches. The holding current is the current level through the triac

below which the triac will turn off. So, the assumption that current through

the triac is higher than the latching current and the holding current means

that the triac stays on once it is fired on. It stays on until the current

through it is zero.

This means that the voltage is supplied to the load for a

fraction of the cycle, determined by how long the triac is on. How long the

triac is on, is, in turn, determined by the delay time between the

zero-crossing and the applying of the triac gating signal.

So, to sum it up, we adjust the voltage or power delivered to

the load by delaying the trigger signal to the triac. One thing to remember is

that, the delivered voltage and power are not linearly related to the firing

phase angle.

There are two voltages here that we are concerned with – the

RMS voltage and the average voltage. The RMS voltage governs the power output

to resistive loads such as incandescent bulbs and resistive heaters. The

average value relates to devices that function on the average voltage level. This

is important because, when testing, your voltmeter will register the average

voltage – and not the true RMS voltage – unless you have a “true RMS

voltmeter”. Most inexpensive voltmeters are not true RMS meters but will

respond to average value changes.

To clarify why power and voltage are not linearly related,

let’s examine the formula relating the two.

So, assuming a constant resistance (be

careful if you’re using incandescent lamps, since they are NOT constant

resistance devices), power is directly proportional to the square of the

voltage. So, if you half the voltage, the power is not halved, but is reduced to

one-fourth the original power! One-fourth power with half the voltage!

Now let’s now go on to the design part – how we’re actually

going to do this.

For

the microcontroller, I’ve chosen the extremely popular PIC 16F877A. However,

since this application requires only a few pins, you can easily use any other

small microcontroller for this purpose, such as PIC 12F675.

The

zero-crossing is done using the bridge-optocoupler method as I had previously

shown. For details regarding the zero-crossing, please go through the article:

Zero crossing detection with PIC16F877A: http://tahmidmc.blogspot.com/2012/10/zero-crossing-detection-with-pic16f877a.html

Now, let’s take a look at the code:

//---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

//Programmer: Syed Tahmid Mahbub

//Compiler: mikroC PRO for PIC v4.60

//Target PIC: PIC16F877A

//Program for phase angle control

//---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

unsigned char FlagReg;

sbit ZC at FlagReg.B0;

void interrupt(){

if (INTCON.INTF){ //INTF flag raised, so external

interrupt occured

ZC = 1;

INTCON.INTF =

0;

}

}

void main() {

PORTB = 0;

TRISB =

0x01; //RB0 input for

interrupt

PORTA = 0;

ADCON1 = 7; //Disable ADC

TRISA = 0xFF; //Make all PORTA

inputs

PORTD = 0;

TRISD = 0; //PORTD all output

OPTION_REG.INTEDG

= 0; //interrupt on falling edge

INTCON.INTF =

0; //clear interrupt flag

INTCON.INTE =

1; //enable external interrupt

INTCON.GIE =

1; //enable global interrupt

while (1){

if (ZC){

//zero crossing occurred

delay_ms(2);

PORTD.B0

= 1; //Send a pulse

delay_us(250);

PORTD.B0

= 0;

ZC = 0;

}

}

}

There isn’t much to it. The zero-crossing is first checked.

After zero-crossing occurs, a small delay is present before the triac is fired.

Here, I’ve used 2ms. So, the triac is fired 2ms after the zero-crossing occurs.

The gating signal is removed 250µs after that. 250µs

is enough time to ensure that the triac has turned on. Even though the gating

signal is removed, the triac stays on until the next zero-crossing as it is a

latching device. Now you may ask, why remove the gating signal? Just keep it on till the next zero-crossing. Well, that'd work too. The problem there would be that, there would be high switching losses of the thyristor. The gate drive resistance would dissipate immense amounts of power - all for no reason, since the triac would be on even if the signal was removed.

The rest of the code should be easy to understand and should be self-explanatory – I’ve added comments to help you understand.

The rest of the code should be easy to understand and should be self-explanatory – I’ve added comments to help you understand.

Now let’s take a look at my circuit setup and then the output waveform using this code:

Fig. 1 - Circuit Diagram (Click on image to enlarge)

You should choose R1 depending on the gate current

requirements of the triac. It must also have a sufficiently high power

dissipation rating. Usually, the instantaneous power may be very high. But

since current flows through the resistor for only 250us (1/40 of a 50Hz half cycle),

the average power is small enough. Usually, 2W resistors should suffice.

Let’s assume we’re using a BT139-600 triac. The maximum required trigger current is 35mA. Although the typical trigger current is lower, we should consider the maximum required trigger current. This is 35mA for quadrants I, II and III. We will only be firing in quadrants I and III. So, that is ok for us – we need to consider 35mA current.

If you aren’t sure what quadrants are, here’s a short

description. First take a look at this diagram:

Fig. 2 - Triac Triggering Quadrants

If you look back again at the diagram, you’ll see that we’re

driving gate from MT2. So, we can say that, with respect to MT1, when MT2 is

positive, so is the gate. With respect to MT1, when MT2 is negative, so is the

gate. From the diagram above, you can see that these two cases are in quadrants

I and III. This is what I meant when I mentioned that we’re driving only in

quadrants I and III.

The driver in the circuit is the MOC3021. This is a random

phase optically isolated triac output driver. When the LED is turned on, the

triac in the MOC3021 turns on and drives the main triac in the circuit. It is a

“random phase” driver meaning that it can be driven on at any time during the

drive signal, as is required for phase angle control. There are other drivers

that only allow drive at the zero-crossing. These cannot be used for phase

angle control as phase angle control requires drive after zero-crossing. For

guaranteeing that the triac is latched, the LED side of the MOC3021 must be

driven with at least 15mA current. The maximum current rating for the LED is

60mA. The peak current rating for the triac is 1A. You should find that we have

stayed within these limits in the design.

Here’s the output waveform:

Fig. 3 - Triac firing with 2 ms delay

Green: Input AC

Yellow: AC Output after phase angle control

Pink: Gate Drive signal

Green: Input AC

Yellow: AC Output after phase angle control

Pink: Gate Drive signal

You can clearly see that before the gate driving signal is

applied, there is no output (illustrated by the flat yellow line).When the gate

driving signal is applied, the triac turns on. There is an output and the triac

stays on till the next zero crossing. After this again, there is no output till

the next gate drive signal is applied.

Now I’ll show you a few more waveforms, with other initial

delays.

Here, the gate is driven 1ms after the zero-crossing:

Fig. 4 - Triac firing with 1 ms delay

Green: Input AC

Yellow: AC Output after phase angle control

Pink: Gate Drive signal

Here, the gate is

driven 4ms after the zero-crossing:

Fig. 5 - Triac firing with 4 ms delay

Green: Input AC

Yellow: AC Output after phase angle control

Pink: Gate Drive signal

Here, the gate is driven 5ms after the zero-crossing:

Fig. 6 - Triac firing with 5 ms delay

Green: Input AC

Yellow: AC Output after phase angle control

Pink: Gate Drive signal

Here, the gate is driven 6ms after the zero-crossing:

Fig. 7 - Triac firing with 6 ms delay

Green: Input AC

Green: Input AC

Yellow: AC Output after phase angle control

Pink: Gate Drive signal

Pink: Gate Drive signal

Now, to finish things off, I’ll show you how to find the RMS

value of the output voltage.

We first need to know how to relate the firing delay with

firing angle. We know that one complete sine wave is 360°. That is 2π

radians. We then need to know that the firing angle α = ωt, where ω = 2πf.

Since, we’re working with 50Hz here, f=50Hz. Thus, ω = 100π.

Just to test this relationship, let’s use t = 0.020 seconds (20ms). Thus α = 100π *

0.020 = 2π, as told before.

So, if we’re firing at a delay of 4ms, that is 4ms after the zero

crossing, the firing angle α = 100 π * (4/1000) = 0.4 π (in radians obviously).

The RMS output voltage is found from the relationship:

So, if we are firing after 4ms, (α = 0.4 π),

the output RMS voltage is:

Remember, at the beginning, I mentioned that the voltage output is not linearly correlated with the firing angle? This is what I meant. Here, the delay is 4ms. So, the triac is on for 60% of the cycle. But the output RMS voltage is 183.2V - 83% of the input voltage. The lack of direct proportionality is evident here. The reason behind this is the shape of the AC - sinusoidal.

Remember, at the beginning, I mentioned that the voltage output is not linearly correlated with the firing angle? This is what I meant. Here, the delay is 4ms. So, the triac is on for 60% of the cycle. But the output RMS voltage is 183.2V - 83% of the input voltage. The lack of direct proportionality is evident here. The reason behind this is the shape of the AC - sinusoidal.

Now, I give you the task of finding the

RMS voltage for the other cases mentioned in this tutorial.

If you want to then find power, you can

use the relationship P = V2/R to find the power. The assumption here

is that the resistance is constant, as was assumed at the beginning of the

tutorial. If the resistance is not constant, power will still vary will

resistance, just not directly proportionally.

Here in this article, I’ve talked about

phase angle control with some background information on triacs. I’ve shown how

to implement phase angle control with a PIC and also how to calculate the RMS

voltage of the output. I hope I’ve been able to explain this extremely important

topic to you clearly and hope that you can now successfully build your own

power control circuits using phase angle control with triacs.

Reference Book:

One of the best books for understanding the theory behind phase angle control is "POWER ELECTRONICS - CIRCUITS, DEVICES AND APPLICATIONS" by Muhammad H. Rashid. If you want to learn more about thyristors or phase angle control, I recommend reading this book for more info.