Ferrite Transformer Turns Calculation for Offline SMPS Half-Bridge Converter

On different

forums, I often find people asking for help in calculating the required turns

for a ferrite transformer they are going to use in offline SMPS half-bridge

converters. The half-bridge topology is very popular for offline converters in

the power range 100W to 500W, sometimes going up to even 1000W. In an offline SMPS

half-bridge converter, the line voltage is rectified and filtered and is then

converted to high frequency with 2 MOSFETs – one in high-side configuration and

the other in low-side configuration. This high frequency high voltage AC is fed

to the ferrite transformer to step down the voltage to low voltage high

frequency AC which is then rectified to DC and filtered to provide clean DC

output. A vital thing to remember is that in a half-bridge converter, the 2

MOSFETs work along with 2 capacitors to create the high voltage high frequency

AC. The configuration of the capacitors, MOSFETs and transformer causes the

transformer to be supplied half the voltage of the rectified DC. This means

that, compared to a full-bridge converter, half the number of turns is required for the primary, but the power output

would be half. Thus power/energy

density is halved.

Now let’s move on to the calculation. Calculation of required turns is actually quite simple and I’ll explain this here.

For explanation, I’ll use an example and go through the calculation process.

Now let’s move on to the calculation. Calculation of required turns is actually quite simple and I’ll explain this here.

For explanation, I’ll use an example and go through the calculation process.

Let’s say

the ferrite transformer will be used in a 250W converter that will be used to charge a 12V lead acid battery. The selected topology

is obviously half-bridge. The power source for the converter is the AC mains.

Here I’ll take that to be 220V RMS, 311V peak, 50Hz. So, you must remember that

the mains AC should be rectified to DC first. Output voltage of the DC-DC

converter stage will be 14V. Switching frequency is 50kHz. The selected core is

ETD44. Remember that the output of the transformer will be high frequency AC

(50kHz square wave in this case). When I refer to an output of low voltage DC

(eg 14VDC mentioned above), this is the DC output obtained after rectification

(using schottky, preferably, or ultrafast recovery diodes configured as full-wave

rectifier) and filtration (using LC filter). Since I plan to use full-wave

rectification (with 2 diodes) at the output, the secondary of the ferrite

transformer will be center tapped.

We must take a maximum and minimum input voltage rating for the converter. For our example, these will be a low line voltage of 150V and a high line voltage of 250V. During operation, the output voltage will stay fixed as the converter is expected to have feedback circuitry.

Vinmin = 150VAC = (150* √2)VDC = 212VDC

We must take a maximum and minimum input voltage rating for the converter. For our example, these will be a low line voltage of 150V and a high line voltage of 250V. During operation, the output voltage will stay fixed as the converter is expected to have feedback circuitry.

Vinmin = 150VAC = (150* √2)VDC = 212VDC

Vinmax

= 250VAC = (250* √2)VDC = 354VDC

Vinnom

= 220VAC = (220* √2)VDC = 311VDC

The formula for calculating the number of required primary turns for a forward-mode converter is:

The formula for calculating the number of required primary turns for a forward-mode converter is:

For our half-bridge transformer, this will be twice the required number of turns, that is, the actual number of primary turns will be half that calculated from the above formula if we use the full voltage, or exactly what is calculated if half the voltage is used. This is because the voltage across the transformer is half the line voltage, as previously mentioned.

So, the actual formula would be:

Npri means number of primary turns; Nsec means number of secondary turns; Naux means number of auxiliary turns and so on. But just N (with no subscript) refers to turns ratio.

For calculating the required number of primary turns using the formula, the parameters or variables that need to be considered are:

- Vin(nom) – Nominal Input Voltage. We’ll take this as 311V. So, Vin(nom) = 311.

- f – The operating switching frequency in Hertz. Since our switching frequency is 50kHz, f = 50000.

- Bmax – Maximum flux density in Gauss. If you’re accustomed to using Tesla or milliTesla (T or mT) for flux density, just remember that 1T = 104 Gauss. Bmax really depends on the design and the transformer cores being used. In my designs, I usually take Bmax to be in the range 1300G to 2000G. This will be acceptable for most transformer cores. In this example, let’s start with 1500G. So Bmax = 1500. Remember that too high a Bmax will cause the transformer to saturate. Too low a Bmax will be under utilizing the core.

- Ac – Effective Cross-Sectional Area in cm2. You will get this information from the datasheets of the ferrite cores. Ac is also sometimes referred to as Ae. For ETD44, the effective cross-sectional area given in the datasheet/specification sheet (I’m referring to TDK E141. You can download it from here: www.tdk.co.jp/tefe02/e141.pdf ). The effective cross-sectional area (in the specification sheet, it’s referred to as Ae but as I’ve said, it’s the same thing as Ac) is given as 175mm2. That is equal to 1.75cm2. So, Ac = 1.75 for ETD44.

Vin(nom)

= 311

f = 50000

Bmax = 1500

Ac = 1.75

Plugging these values into the formula:

Plugging these values into the formula:

Npri = 29.6

We won’t be using fractional windings, so we’ll round off Npri to the nearest whole number, in this case, rounded up to 30 turns. Now, before we finalize this and select Npri = 30, we better make sure that Bmax is still within acceptable bounds (it will be since this is such a minor percentage change, but I’ll show this anyways so that you know what to do, just in case). As we’ve increased the number of turns from the calculated figure (up to 30 from 29.6), Bmax will decrease very slightly. We’ll now figure out just how much Bmax has decreased.

Bmax = 1481

The new value of Bmax is well within acceptable bounds and so we can proceed with Npri = 30.

So, we now know that for the primary, our transformer will require 30 turns.

In any design, if you need to adjust the values, you can easily do so. But always remember to check that Bmax is acceptable.

- I’ve started off with a set Bmax and gone on to calculate Npri from there. You can also assign a value of Npri and then check if Bmax is okay. If not, you can then increase or decrease Npri as required and then check if Bmax is okay, and repeat this process until you get a satisfactory result. For example, you may have set Npri = 20 and calculated Bmax and decided that this was too high. So, you set Npri = 30 and calculated Bmax and decided it was okay. Or you may have started with Npri = 40 and calculated Bmax and decided that it was too low. So, you set Npri = 30 and calculated Bmax and decided it was okay.

Naturally, feedback will be implemented to keep the output voltage fixed with line and load variations – changes due to mains voltage change and also due to load change. So, some headroom must be left for feedback to work. So, we’ll design the transformer with secondary rated at 16V. This headroom compensates for voltage drops due to output rectifier diodes. Feedback will just adjust the voltage required by changing the duty cycle of the PWM control signals. Besides that, the headroom also compensates for some of the other losses in the converter and thus compensates for the voltage drops at different stages – for example, in the MOSFETs, in the transformer itself, in the output inductor, etc.

This means that the output must be capable of supplying 14V with input voltage equal to 212VDC and also input voltage equal to 354VDC. For the PWM controller, we’ll take maximum duty cycle to be 98%. The gap allows for dead-time.

At minimum input voltage (when Vin = Vinmin), duty cycle will be maximum. Thus duty cycle will be 98% when Vin = 212VDC = Vinmin. At maximum duty cycle = 98%, average voltage to transformer = 0.98 * 0.5 * 212V = 103.88V.

So, voltage ratio (primary : secondary) = 103.88V : 16V = 6.493

Since voltage ratio (primary : secondary) = 6.493, turns ratio (primary : secondary) must also be 6.493 as turns ratio (primary : secondary) = voltage ratio (primary : secondary). Turns ratio is designated by N. So, in our case, N = 6.493 (I’ve taken N as the ratio primary line voltage : secondary).

Npri = 30

Nsec = Npri / N = 30 / 6.493 = 4.62

Round off to the nearest whole number. Nsec = 5

Now, notice how this rounding up is not an insignificant rounding up. So, let’s try to keep Nsec = 5 and adjust Npri again.

Npri = N * Nsec

Npri

= 5 * 6.493 = 32.5 = 33 (rounded off to the nearest integer)

Now let’s check if Bmax is okay with Npri = 33, ie, if Bmax is within acceptable bounds.

Now let’s check if Bmax is okay with Npri = 33, ie, if Bmax is within acceptable bounds.

Bmax = 1346

Bmax = 1346 is okay. So, Npri = 33 and Nsec = 5. Thus 5 + 5 turns are required for the secondary. With proper implementation of feedback, a constant 12VDC output will be obtained throughout the entire input voltage range of 150VAC to 250VAC.

Of course, notice here that Bmax is very small and can be increased to reduce the required turns. So, let’s reduce Nsec from 5 to 4.

Nsec

= 4

Npri

= N * Nsec = 6.493 * 4 = 25.97 = 26 (rounded off to nearest integer)

Checking Bmax

again:

Bmax = 1709

Here, one thing to note is that even though I took 98% as the maximum duty cycle, maximum duty cycle in practice will be smaller since our transformer was calculated to provide 16V output. In the circuit, the output will be 16V (transformer output will be 14V + Voltage drop of diode), so the duty cycle will be even lower. However, the advantage here is that you can be certain that the output will not drop below 12V even with heavy loads since a large enough headroom is provided for feedback to kick in and maintain the output voltage even at high loads and low line voltages.

If any auxiliary windings are required, the required turns can be easily calculated. Let me show with an example. Let’s say we need an auxiliary winding to provide 17.5V. I know that the output 14V will be regulated, whatever the input voltage may be, within the range initially specified (Vinmin to Vinmax – 150VAC to 250VAC). So, the turns ratio for the auxiliary winding can be calculated with respect to the secondary winding. Let’s call this turns ratio (auxiliary : secondary) NA.

NA = Naux / Nsec = (Vaux+Vd)/ (Vsec + Vdsec). Vdsec is the output diode forward drop (at the secondary). Vd is the output diode forward drop at the auxiliary. Let’s assume that in our application, schottky rectifiers with Vd = 0.5V is used.

So, NA = 18.0V/14.5V = 1.24

Naux / Nsec = NA

Here, one thing to note is that even though I took 98% as the maximum duty cycle, maximum duty cycle in practice will be smaller since our transformer was calculated to provide 16V output. In the circuit, the output will be 16V (transformer output will be 14V + Voltage drop of diode), so the duty cycle will be even lower. However, the advantage here is that you can be certain that the output will not drop below 12V even with heavy loads since a large enough headroom is provided for feedback to kick in and maintain the output voltage even at high loads and low line voltages.

If any auxiliary windings are required, the required turns can be easily calculated. Let me show with an example. Let’s say we need an auxiliary winding to provide 17.5V. I know that the output 14V will be regulated, whatever the input voltage may be, within the range initially specified (Vinmin to Vinmax – 150VAC to 250VAC). So, the turns ratio for the auxiliary winding can be calculated with respect to the secondary winding. Let’s call this turns ratio (auxiliary : secondary) NA.

NA = Naux / Nsec = (Vaux+Vd)/ (Vsec + Vdsec). Vdsec is the output diode forward drop (at the secondary). Vd is the output diode forward drop at the auxiliary. Let’s assume that in our application, schottky rectifiers with Vd = 0.5V is used.

So, NA = 18.0V/14.5V = 1.24

Naux / Nsec = NA

Naux = Nsec * NA = 4 * 1.24 = 4.96

Let’s round off Naux to 5. Since the rounding up is very small (from 4.96 to 5), the output voltage will be pretty close to the desired voltage, but I'll just show you how to calculate what the output voltage is.

(Vaux

+ Vd) / (Vsec + Vdsec) = NA = Naux

/ Nsec = 5 / 4 = 1.25

(Vaux

+ Vd) = (Vsec + Vdsec) * NA = 14.5V

* 1.25 = 18.13V

Vaux

= 17.63V

That is great for an auxiliary supply. If in your designs, you ever find that Vaux is far too off the required voltage, a simple voltage regulator (using 78XX for example) should be used to provide the stable auxiliary voltage.

Another option is to recalculate Npri and Nsec to accommodate for a near accurate auxiliary voltage but you can just use a voltage regulator to simplify things. After all, the voltage regulator will keep the output voltage regulated stable.

So, there we have it. Our transformer has 26 turns for primary, 4 turns + 4 turns for secondary and 5 turns for auxiliary.

Here’s our transformer:

That is great for an auxiliary supply. If in your designs, you ever find that Vaux is far too off the required voltage, a simple voltage regulator (using 78XX for example) should be used to provide the stable auxiliary voltage.

Another option is to recalculate Npri and Nsec to accommodate for a near accurate auxiliary voltage but you can just use a voltage regulator to simplify things. After all, the voltage regulator will keep the output voltage regulated stable.

So, there we have it. Our transformer has 26 turns for primary, 4 turns + 4 turns for secondary and 5 turns for auxiliary.

Here’s our transformer:

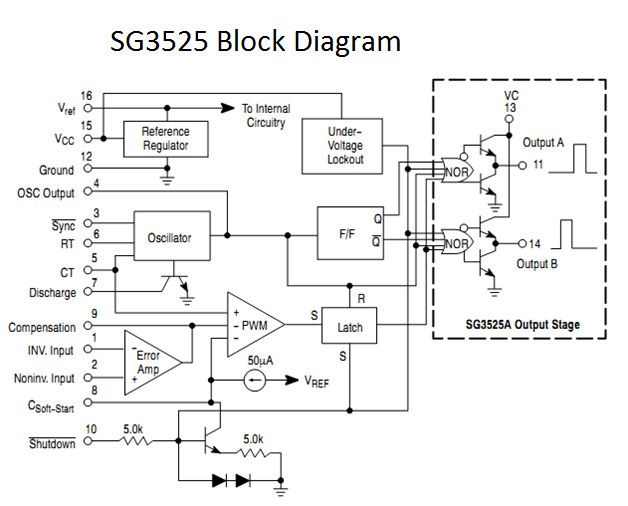

Here’s the transformer at work in a circuit (block diagram):

Calculating required number of turns for a transformer for an offline SMPS half-bridge converter is actually a simple task and I hope that I could help you understand how to do this. I hope this tutorial helps you in your ferrite transformer designs for offline SMPS half-bridge converters. Do let me know your comments and feedback.